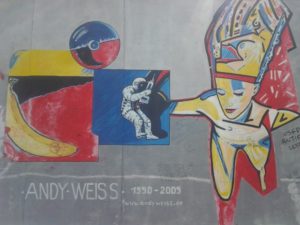

WEST LONG BRANCH, NJ– Annually, millions of people from around the world visit Germany’s famous East Side Gallery, a nearly mile-long stretch of the original Berlin Wall that has not only been left standing for decades but has also become an illustrious canvas for eclectic street art and graffiti murals by international artists. With this year’s momentous 25th anniversary of the Berlin Wall, the decades-old argument of whether or not graffiti should be considered an art form has once again reared its head.

Berlin’s celebrated and iconic memorial has prompted the question of why graffiti cannot be celebrated elsewhere. It may be because, graffiti, which can include the use of spray paint, stencils, and stickers in public spaces, has traditionally been associated with gang members and delinquents. This deeply rooted connotation is one of the main obstacles that prevents the understanding of graffiti as art here in the United States.

Heather Mac Donald, a Thomas W. Smith Fellow at the Manhattan Institute who contributed her insights on graffiti to the New York Times’ Opinion Pages in early December, refuses to accept any form of graffiti as art because of this negative association.

“The question ‘When does graffiti become art?’ is meaningless,” said Mac Donald. “Graffiti is always vandalism. By definition it is committed without permission on another person’s property, in an adolescent display of entitlement.”

But what if this very definition of graffiti is the problem? What if, like a museum portrait or new tattoo that needs retouching, the definition Mac Donald mentions is desperately in need of an update that fits this day and age?

Many have already been able to look past graffiti’s link to vandalism and acknowledge how crucial it is to urban landscapes, especially with the new popularity of street artists like Banksy and Blek le Rat. An article by the BBC features one of these progressive individuals, “Felix” of reclaimyourcity.net, who argues that graffiti helps others do exactly what his website name suggests: to reclaim their city.

“Graffiti and street art are the only ways that people can interact with public spaces actively,” said Felix. “These art forms can, for example, express emotions, give critique on current politics or society, or offer venues for public art.”

“Therefore,” he continues, “they create a space for communication and discourse, where private experiences can be made visible, and where critical, personal or artistic messages can be passed onto others outside the artists’ immediate circles.”

This is especially true for the East Side Gallery, which has been able to powerfully showcase pain, nostalgia, joy, inspiration, and so much more in a public venue and communicate the story of Berlin to those who may never have seen it otherwise.

Yet the same goes for those who live in neighborhoods right by Monmouth University. Michael Hamilton, a senior currently studying political science who can see tags and spray painted stencils from his window, does not mind his town’s graffiti.

“Seeing the graffiti around town actually doesn’t bother me at all,” said Hamilton. “In fact, I think of it as art that gives me a lot of insight into the people who live around here and that lets me hear their voices—the same way art at a museum would. Even when the graffiti on the walls doesn’t necessarily mean anything to me, its vibrancy lights up any dreary day.”

Against all odds, proponents of street art, including Felix and Hamilton, and its opponents, like Mac Donald, can coexist if a compromise is reached. MatadorNetwork compiled a list of areas around the world where streets and even city blocks have been designated for street artists and individuals who want to express themselves through graffiti without being harassed by the police. Among these places are Melbourne, Australia, Taipei, Taiwan, and Zurich, Switzerland. Perhaps the resurfaced graffiti debate will allow more cities in the United States to join the ranks of these cities.